INDR commentary, Anders Schmidt Vinther

The steroid ”epidemic” myth

Anders Schmidt Vinther, Aalborg Antidoping, Department of Health and Culture, Aalborg Municipality, Denmark

The media’s love affair with sensationalism

When the reality star Spencer Matthews appeared in the TV show Good Morning Britain (GMB) on July 13 2016 and talked openly about his previous and ”mistaken” use of anabolic steroids, the underlying theme was as clear as it was predictable: Steroid use is a threat to public health, and, more importantly, the number of users is increasing. Matthews, along with the general practitioner Dr. Hilary Jones, were invited to comment on the alleged explosion of young men using steroids for performance- and image-enhancing purposes [1].

In this steroid edition of GMB Investigates, needle exchanges and drug charities across the UK were contacted for information on the extent of the steroid problem. The investigation revealed among other things that the number of steroid users accessing needle exchanges in South Wales has increased eightfold (from 269 to 2,161 visitors) during the past five years, that the use of steroids and image-enhancing drugs (SIEDs) in Cheshire and Merseyside in England is now 20 % higher than it was just a year ago, and that boys as young as 14 are taking steroids.

These apparently alarming results were quickly picked up by other news media who passed on the message that steroid use is on the rise, all arguing that it has now reached ’epidemic’ proportions [2][3][4]. For instance, an article in the popular magazine Men’s Health set out to ’explore Britain’s anabolic appetite’, and claimed that ’… those who are taking them [steroids] are among a growing herd. In fact, they’re perfectly normal.’ [4].

Puncturing the myth

The idea that the non-medical use of anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) is increasing is frequently accepted without reservations among journalists driven by sensationalism, as witnessed above, as well as academics seeking to justify their research. For instance, one study described the world population of AAS users as ‘growing’ without substantiating the claim [5]. Moreover, a Swedish doping scholar even argued recently that the abuse of AAS is the second largest drug abuse problem in Sweden, only surpassed by alcohol abuse, without referring to any evidence other than experts’ opinions (including his own of course) [6].

Unfortunately claims like these are rarely questioned, hardly ever substantiated with evidence, and the idea that AAS use has escalated over the years seems to have acquired the status of ’common knowledge’ among some health professionals, drug use counsellors and people in fitness and strength training environments.

Notwithstanding how appealing this idea might be, it is based on false premises and lack of evidence. In fact, when you look at the evidence that is available at present, it seems to support the opposite conclusion, namely that AAS use has remained relatively stable over the past two decades, with a slight decrease from the turn of the millennium and into the 21st century – a story that is indeed very different from the usual narrative.

It goes without saying that it does not follow from an increase in the number of AAS users visiting needle exchanges that the prevalence of AAS use has actually increased, just as nothing can be inferred about the prevalence of doping use in sport from the number of positive samples in one sport. So the GMB investigation, like most other media reports, does not at all contribute to clarifying the issue. Likewise, it is difficult to conclude anything about the development of drug use prevalence from statistics on drug seizures, since these numbers depend on several other factors such as allocation of resources and prioritization of tasks among the police and customs.

What do we really know about the development of AAS use?

As a matter of fact, there exist no convincing long-term data to support the notion that AAS use has increased during the past two decades. In a recent meta-analysis, the global lifetime prevalence of AAS use was estimated to 3,3 %, with no significant difference between the two periods 1990-1999 (2,9 %) and 2000-2013 (3,2 %), and with no significant relationship between publication year and prevalence rate. It is therefore difficult to understand why the authors state the following in the discussion (on pages 393-394): “our finding that the prevalence rate of AAS use is slightly higher in recent times (after 2000) than in the 1990s suggests that nonmedical use of AAS has steadily increased since the 1990s” [7].

Since questions on AAS use are absent from most international drug surveys that have been conducted systematically on a long-term basis (e.g. UNODC’s World Drug Report and the European Drug Report), it is difficult to accurately determine how the global prevalence of AAS use has developed. However, there is one European and a some national surveys (primarily from the US, UK, Sweden and Australia) that have measured the prevalence of AAS use among different user populations across a large enough time span – some since 1991 – to serve as the best available evidence for the matter in question.

The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) have published data on alcohol and drug use (including AAS) among European school children aged 15-16 every four years since 1995, with the latest report published October 20 this year. According to this survey, the lifetime prevalence of AAS use has ranged from 0 to 5 % in the participating European countries during the past two decades (1995-2015), but no cross-national patterns clearly emerge from the data. Overall, the prevalence is fairly low in the vast majority of the countries. In the last 20 years it has typically oscillated between 0 and 2 %, but whereas some countries (e.g. Bulgaria, Greece, Ireland and Poland) have experienced a slight increase, others (e.g. Croatia, Latvia, Slovenia and the UK) have experienced a decrease [8].

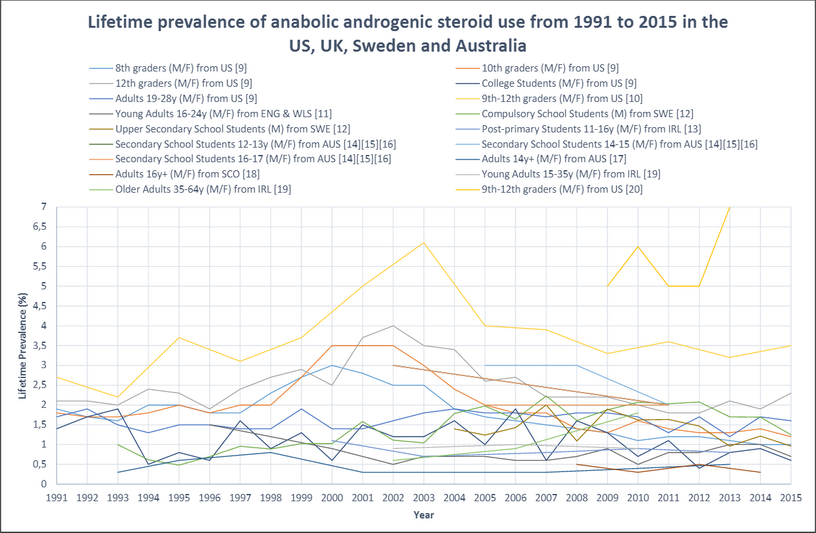

The results from the national drug surveys, most of which have been conducted more frequently (e.g. every year or every second year) than the ESPAD survey, reveal a different and more consistent picture of the development of AAS use as depicted in the figure below. Although there have been no drastic fluctuations in the use of AAS between 1991 and 2015, a large minority of the surveys found that AAS use began to increase in the beginning of the 1990s, levelled off at the turn of the millennium, and then decreased in the 21st century [9][10][11][12]. Other surveys found little or no change at all [13][14][15][16][17][18][19], while only two surveys, one conducted among older adults aged 35-64 [19] and one among school children in grades 9 through 12 in the period from 2009 to 2013 [20], found an increase in the use of AAS.

Can we trust the data?

These data should of course be interpreted with caution. First, the use of AAS might in fact have increased despite the evidence demonstrating the contrary. Most of the surveys used for the above figure are conducted in populations (e.g. school children and the general population) that are different from the typical AAS using population (mostly young, male gym users), and it is therefore not unlikely that the use of AAS has increased in the latter population while having simultaneously decreased in the former two.

Second, false negative responses may result in an underestimation of the true prevalence (e.g. due to recall bias or social desirability, the latter being a more likely explanation), a phenomenon well known from the study of doping use in sport. On the other hand, false positive responses might explain differences in the opposite direction. For instance, in the 2011 ESPAD report, up to 3,1 % answered that they had once taken the drug ’relevin’ (which doesn’t exist), a ’dummy drug’ invented and introduced to reveal the number of false positives [8].

Third, changes in the formulation of the question on AAS use may have influenced how respondents understood and subsequently answered the question. However, the surveys reporting to have changed the question at some point in time made only minor revisions that are unlikely to have had any significant influence on the results [9][12].

Fourth, there might be national variations in the prevalence of AAS use and how it has developed due to different social, cultural and institutional settings. But the sparse evidence that is available at the moment (due to lack of long-term data) mainly from European countries such as Norway, Finland, Denmark, Germany, Belgium, Netherlands, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece does not allow for such comparisons.

This dispute on numbers is not only a matter of finding the correct prevalence rate. Exaggerating the problem may be a problem in itself. A recent large-scale study among university and college students from seven EU countries demonstrated that perceived peer use of and attitudes toward alcohol predicted personal behavior and attitudes [21]. If these results can be generalized to AAS use, exaggerating the extent of the problem may actually contribute to increase the number of users – an unintended consequence that will undeniably do more harm than good.

It is important to stress that I am not trying to downplay the public health issues related to AAS use. Since it was not before the beginning of the 1980s that AAS use became widespread outside elite sport, we have yet to witness the long-term medical consequenses among former and current AAS users. However, it is widely acknowledged that there are a wide range of adverse health consequences associated with AAS use such as cardiovascular disease, suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular (HPT) function, depression and dependence [22].

Neither am I claiming that AAS use is a phenomenon that belongs to the past. Although the evidence that is available at the moment does not support the claim that steroid use has escalated over the years, a recent study from the UK indicates that steroid use has become a larger challenge to public health during the past two decades. This is evidenced by an increase in the number of steroid users visiting needle and syringe programmes (NSPs) in the period from 1995 to 2015, and a simultaneous explosion in the total number of dispensed syringes (from 14.293 to 139.956) as well as in the number of dispensed syringes per individual (from 26 to 57) [23].

Thus, the use of AAS clearly poses a serious threat to global public health. Policy makers, health professionals and people working with the prevention of substance use should take the physical, psychological and social consequences of AAS use seriously. But until convincing evidence becomes available, the idea that steroid use is an ’epidemic on the rise’ remains nothing more than a myth.

References

1. Retrieved from: http://www.itv.com/goodmorningbritain/news/spencer-matthews-investigates-britains-steroid-epidemic-for-gmb

2. Retrieved from: http://www.mirror.co.uk/lifestyle/health/uk-facing-steroids-epidemic-needle-8399766

3. Retrieved from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-3686305/Self-confessed-steroid-user-Spencer-Matthews-reveals-UK-grips-epidemic-million-taking-drugs.html

4. Retrieved from: http://www.menshealth.co.uk/building-muscle/big-read-britains-steroid-epidemic

5. Kanayama, G. et al. (2015). Prolonged hypogonadism in males following withdrawal from anabolic-androgenic steroids: an underrecognized problem. Addiction, 110(5), 823-831.

6. Retrived from: http://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/sormland/allt-fler-dopar-sig-storsta-missbruket-efter-alkohol

7. Sagoe, D. et al. (2014). The global epidemiology of anabolic-androgenic steroid use: a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Annals of Epidemiology, 24, 383-398.

8. ESPAD Report 2015: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. All reports can be retrieved from: http://www.espad.org/

9. Miech, R. A. et al. (2016). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. Retrieved from: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2015.pdf

10. Kann, L. et al. (2015). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016;65(6). Data retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/2015_us_drug_trend_yrbs.pdf

11. Lader, D. (2016). Drug Misuse: Findings from the 2015/2016 Crime Survey for England and Wales: Statistical Bulletin 07/16. Home Office. Data retrived from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/542585/drug-misuse-1516-tabs.xls

12. Gripe, I. (2015). Skolelevers drogvanor 2015. Centralförbundet för alkohol- och narkotikaupplysning. Data retrieved from: http://www.can.se/globalassets/tabellbilaga/tabellbilaga.xlsx

13. Young Persons’ Behaviour & Attitudes Survey (2000-2013). Central Survey Unit, Northern Ireland Statistics & Research Agency. Retrieved from: www.csu.nisra.gov.uk/survey.asp96.htm

14. White, V., & Smith, G. (2005). Australian secondary school students’ use of over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2005. Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer. The Cancer Coucil Victoria. Retrieved from: http://webarchive.nla.gov.au/gov/20110309154033/http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/mono60

15. White, V., & Smith, G. (2009). Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2008. Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer. The Cancer Coucil Victoria. Retrieved from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/Content/2C4E3D846787E47BCA2577E600173CBE/$File/school08.pdf

16. White, V., & Bariola, E. (2012). Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2011. Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer. The Cancer Council Victoria. Retrived from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/BCBF6B2C638E1202CA257ACD0020E35C/$File/National%20Report_FINAL_ASSAD_7.12.pdf

17. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2014. National Drug Strategy Household Survey detailed report 2013. Drug statistics series no. 28. Cat. no. PHE 183. Canberra: AIHW. Data retrieved from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129548784

18. Robertson, L. (2016). Scottish Crime and Justice Survey 2014/15: Drug Use. Scottish Government Social Research. Retrieved from: http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0050/00502173.pdf

19. National Advisory Comittee on Drugs (NACD) & Public Health Information and Research Branch (PHIRB) (2012). Drug Prevalence Survey 2010/11: Regional Drug Task Force (Ireland) and Health & Social Care Trust (Northern Ireland) Results. Retrieved from: http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/drug_use_ireland_new1.pdf

20. Partnership for Drug-Free Kids (2013). The Partnership Attitude Tracking Study: Teens & Parents. Retrieved from: http://www.drugfree.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PATS-2013-FULL-REPORT.pdf

21. McAlaney, J. et al. (2015). Personal and perceived peer use of and attitudes toward alcohol among university and college students in seven EU countries: Project SNIPE. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(3), 430-438.

22. Pope, H.G. et al. (2014). Adverse health consequences of performance-enhancing drugs: An endocrine society scientific statement. Endocrine Reviews, 35, 341-375.

23. McVeigh, J. & Begley, E. (2016). Anabolic steroids in the UK: an increasing issue for public health. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, DOI: 10.1080/09687637.2016.1245713.

a